U of A topped $257M in total funding for active research partnerships that included Native tribes in fiscal year 2025

Chris Richards/University Communications

Updated Oct. 15, 2025.

Daelyn Nez's ambitions as a researcher could lead her anywhere, but she plans to eventually return home to Indian Wells, Arizona, as a veterinarian.

That's where Nez grew up, on the Navajo Nation, in a ranching and rodeo family surrounded by horses, cattle and other livestock. She wouldn't have it any other way.

Daelyn Nez

Courtesy of Daelyn Nez

"My dad always told us, 'This place is going to be your first teacher. It's going to teach you everything you'll need to know in order to be successful when you get older,'" Nez said. "That's kind of how I was brought up."

As a junior studying animal sciences in the University of Arizona College of Agriculture, Life and Environmental Science, Nez is focused on giving back to the animals and way of life that taught her how to succeed. She intends to apply to the U of A College of Veterinary Medicine, among other vet schools, when she completes her undergraduate degree.

Perhaps it's fitting then that Nez has spent her summer at home, working in a research lab at Diné College, the tribal college that serves the Navajo Nation. Nez is one of several students participating in the Bridge to STEAM "Come Back Home" Program, a partnership between Diné College and the Indigenous Resilience Center that provides paid research internships to tribal students who have transferred to the U of A.

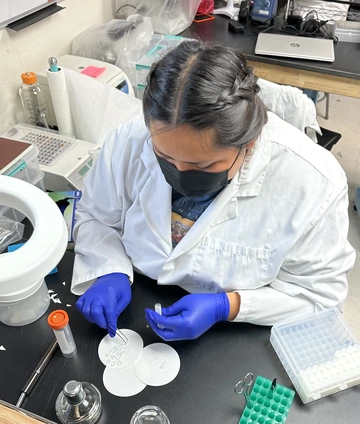

During her internship, Nez has focused on plants – specifically, trying to understand more about fungal endophytes, the microscopic fungi that grow inside the tissues of native plants on the Nation. Much of her day-to-day work has involved collecting samples of these fungi, then trying to grow them in the lab for closer study.

The process reminds Nez of her grandmother, who collected sage, Navajo tea and other plants, always keeping them on hand for medicinal and other uses. While studying plants may seem like a bit of a departure from animal science, Nez said the connections are clear.

"We live in a world where living things have relationships with each other. It's not just the animal by itself – the animal is in an environment and within that environment, you have the soil, the plants, the water," she added. "I went into this thinking, if we really want to take care of our animals, this is something I can look into."

Tribal research is a key investment

Nez spent her summer working in a research lab at Diné College, trying to understand more about the microscopic fungi that grow inside the tissues of native plants on the Navajo Nation.

Courtesy of Daelyn Nez

Tribal research partnerships such as the one that brought Nez home for the summer are common for the University of Arizona. In fiscal year 2025, the university counted more than $257 million in funding for active research partnerships that involved tribal communities, according to a database by the university's Native Peoples Technical Assistance Office, known as NPTAO.

The $257 million figure accounts for the total funding allotment for projects that in some way involved tribal communities, including multi-year projects that were active during fiscal year 2025.

"This just shows how much collaboration and partnership our university has with Native Nations," said Levi Esquerra, special adviser for Native American affairs in the Office of the Provost. "We respect sovereign nations and we've put procedures in place to ensure they receive the benefits of the research we do."

The database represents an array of research across campus done in partnership with and for hundreds of tribal communities, especially Arizona's 22 recognized tribes. Projects represented in the database include a federally funded center to revitalize Native languages in the College of Education; a program from the Southwest Institute for Research on Women to address substance abuse among Native American women; a video dictionary of tribal sign languages, also in the College of Education; a project in the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health to design protocols and best practices for managing global Indigenous data; and more.

The database is another marker of the university's commitment to Native Nations and their students, said Tessa Dysart, assistant vice provost for Native American initiatives. The university counted more than 2,000 Native students among its total enrollment of about 57,000 last fall, representing about 200 tribes.

"As an R1 research institution, our students come here hoping to do research," Dysart said, referring to the U of A's designation as a leading research institution. "It's exciting that we can offer our Native students an experience that connects deeply to who they are and supports their communities."

A legacy of tribal research data

NPTAO's database also represents a longstanding commitment by the university's research enterprise to build relationships with tribes that respect their sovereignty, said Claudia Nelson, the director of NPTAO, which is a unit in the Office of Research and Partnerships.

The university's record-keeping on its tribal research partnerships goes back to at least the 1980s, said Nelson, who began at the university in the 1990s in what was then called the Office of Indian Programs. After earning a master's degree at the U of A in American Indian Studies and spending several years consulting with tribes, she took it upon herself to continue collecting and archiving data about the university's research with tribes.

"I just began doing the collection myself," Nelson said. "I just thought from my experience at the time that it should be done. That's when we began to get serious about tribal consultation."

In the 30 years since, Nelson and her team have built the database into a comprehensive source to understand how university research serves tribal communities. What was once a static archive of project descriptions and funding figures is now a searchable database powered by data from Sponsored Projects Services and University Analytics and Institutional Research. Users can search the database by keyword and filter by the tribal affiliation, the projects' lead college or unit, and principal investigators.

Kelly Eitzen Smith, a research associate in NPTAO, helped develop the database's current iteration and now manages it along with NPTAO's other websites and tools. Smith reviews each project designated to have a tribal research component and will reach out to principal investigators to clarify the project description, if necessary.

"I think it's interesting, just the number of projects that come through that have a Native engagement component," Smith said, noting that more than 80 proposed projects came through Sponsored Projects Services or the university's Institutional Review Board in the first six months of 2025.

For Nez, who will wrap up her internship on the Navajo Nation this month, research partnerships are crucial to rebuild trust between Native communities and institutions.

"Partnerships like these are so important because they help build the trust, and they help build the trust in the right way – with respect for our culture, and having the research uplift Native voices," said Nez, who is this academic year's Miss Native University of Arizona. "When they're done right, these collaborations can address real issues that our Native communities face. Research that values Indigenous knowledge will co-create solutions."