The monster hiding in plain sight: JWST reveals cosmic shapeshifter in the early universe

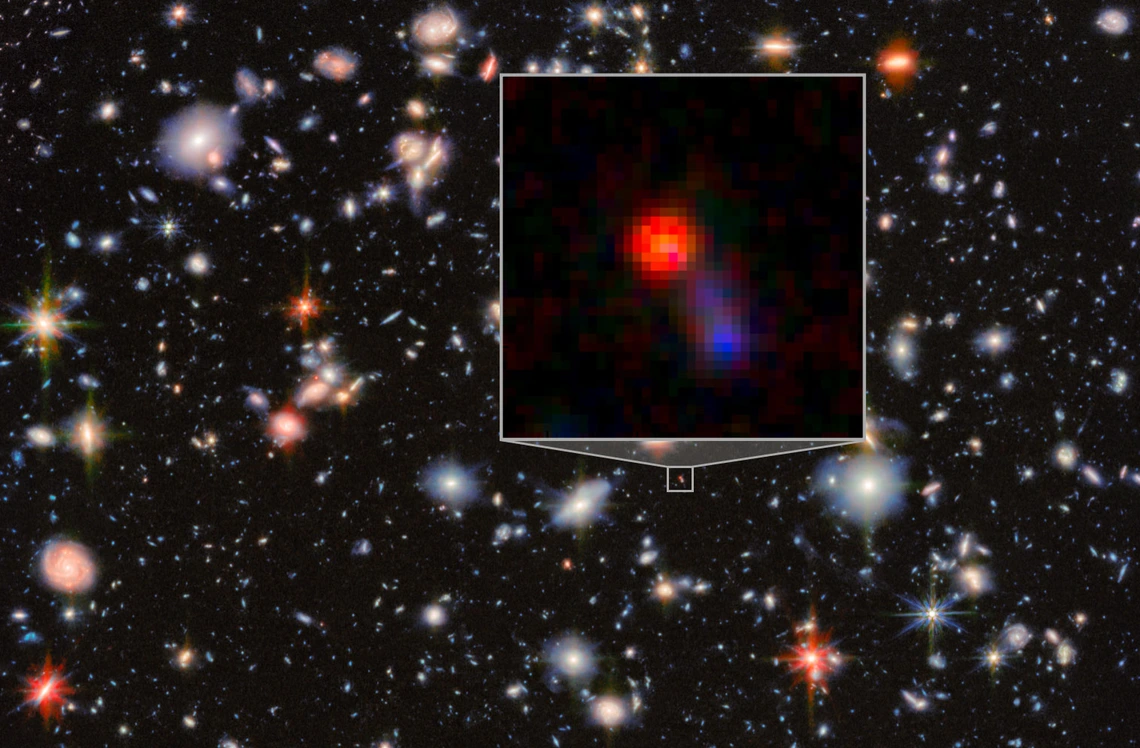

Covering a tiny patch of sky spanning less than a tenth of the full moon, the famous "Hubble eXtreme Deep Field" image revealed thousands of galaxies, including objects from the universe infancy. The James Webb Space Telescope observed the same region over three years. U of A researchers zoomed in on the galaxy reported in this study (inset), captured when the universe was only 800 million years old. The team found that even at its young age, it already harbored a supermassive black hole, shrouded in dust.

NASA, ESA, G. Illingworth, D. Magee, and P. Oesch (University of California, Santa Cruz), R. Bouwens (Leiden University), and the HUDF09 Team

In a glimpse of the early universe, astronomers have observed a galaxy as it appeared just 800 million years after the Big Bang – a cosmic Jekyll and Hyde that looks like any other galaxy when viewed in visible and even ultraviolet light but transforms into a cosmic beast when observed at infrared wavelengths.

This object, dubbed Virgil, is forcing astronomers to reconsider their understanding of how supermassive black holes grew in the infant universe.

The discovery, led by University of Arizona Steward Observatory astronomers George Rieke and Pierluigi Rinaldi (now with the Space Telescope Science Institute) and published in The Astrophysical Journal, examines a known galaxy named Virgil, but exposes its hidden nature: a supermassive black hole in the galaxy's center accreting material at an extraordinary rate, with its energy output obscured by thick veils of dust. The inferred black hole mass is far larger than its host galaxy should be able to support, placing Virgil among the so-called "overmassive" black holes that challenge current models of how black holes formed in the early universe.

The discovery challenges prevailing theories about how supermassive black holes and galaxies grew together. Before NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers believed that galaxies formed first and gradually nurtured black holes in their cores, with both growing in lockstep over cosmic time.

"JWST has shown that our ideas about how supermassive black holes formed were pretty much completely wrong," said Rieke, a Regents Professor of astronomy and a pioneer of infrared astronomy. "It looks like the black holes actually get ahead of the galaxies in a lot of cases. That's the most exciting thing about what we're finding."

Virgil belongs to a mysterious class of objects astronomers call Little Red Dots, or LRDs. The expansion of space between us and distant cosmic objects stretches their light, shifting it toward red, or longer, wavelengths by the time it reaches us.

LRDs are a group of compact, extremely red sources discovered by JWST that have sparked debate among astronomers. These luminous dots appeared in large numbers around 600 million years after the Big Bang, only to all but disappear about 1.5 billion years later. Theories to explain them range from star formation to exotic physics such as matter-antimatter annihilation.

Virgil is the reddest object in the entire Little Red Dot population discovered to date. If Little Red Dots formed in abundance in the early universe, what did they become? Nothing can leave our universe, so their descendants must exist somewhere today. This latest discovery advances the scientific community's understanding of early black hole evolution and might point toward a potential solution to the mystery.

The discovery also puts U of A-led technology in the spotlight. Virgil's true nature only became apparent through observations with JWST, specifically its Mid-Infrared Instrument, or MIRI, for which Rieke is the Science Team Lead. When using data from only JWST's Near Infrared Camera, or NIRCam, or Near-Infrared Spectrograph, or NIRSpec – both of which cover only up to the optical wavelengths in the early universe – astronomers would classify Virgil as an entirely ordinary star-forming galaxy.

The paper shows that some of the universe's most extreme objects may be hiding in plain sight – detectable only when tuning instruments to detect infrared wavelengths, which is a light spectrum invisible to the human eye. These longer wavelengths exist where dust-shrouded phenomena reveal themselves.

"Virgil has two personalities," said Rieke. "The UV and optical show its 'good' side – a typical young galaxy quietly forming stars. But when MIRI data are added, Virgil transforms into the host of a heavily obscured supermassive black hole pouring out immense quantities of energy."

"MIRI basically lets us observe beyond what UV and optical wavelengths allow us to detect," said Rinaldi, who focused his doctoral research on MIRI observations. "It's easy to observe stars because they light up and catch our attention. But there's something more than just stars, something that only MIRI can unveil."

The implications extend beyond individual objects like Virgil. Many high-redshift surveys with JWST obtain deep imaging with NIRCam but only short exposures ("shallow observations") with MIRI, due to the considerable time required to gain a deeper view. The longer the total exposure time, the more sensitive the imaging, allowing very faint or distant objects like Virgil to come into view.

This means astronomers may be systematically missing a hidden population of dust-obscured black holes that could play a significant role in cosmic history – potentially even contributing to the reionization of the universe during cosmic dawn: the turning point around 100-200 million years after the Big Bang "when the universe decided to light up with stars," Rinaldi said.

Remarkably, no other source with Virgil's extraordinary traits has been reported at such early cosmic times. But the team suspects this may reflect observational limitations rather than true rarity. "Are we simply blind to its siblings because equally deep MIRI data have not yet been obtained over larger regions of the sky?" Rinaldi asked.

The team looks forward to making further deep MIRI observations in the future, which would reveal whether Virgil is truly alone or represents the tip of an iceberg. "JWST will have a fascinating tale to tell as it slowly strips away the disguises into a common narrative," said Rinaldi.