Alpha Centauri, sun's closest stellar neighbor, likely harbors giant planet

This artist’s concept shows what a gas giant orbiting Alpha Centauri A could look like. Observations of the triple star system Alpha Centauri using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope indicate the potential gas giant, about the mass of Saturn, orbiting the star by about two times the distance between the Sun and Earth.

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Robert L. Hurt (Caltech/IPAC)

A giant planet could be orbiting a star in the stellar system closest to our own sun, a slice of the galaxy that has long been a compelling target in the search for worlds beyond our solar system.

The finding comes from newly published observations of the Alpha Centauri triple star system that researchers at the University of Arizona Steward Observatory helped make with NASA's James Webb Space Telescope.

The first hint of a possible planet around the Alpha Centauri system, just 4 light years away from our sun, was reported in a 2021 paper led by Kevin Wagner, an assistant research professor at Steward Observatory and a co-author on the new publication. According to Wagner, the discovery is shaping up to be "one of the most exciting results in astronomy of the decade."

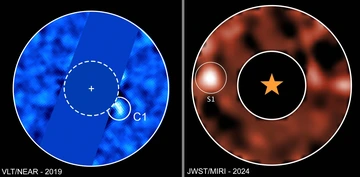

Left panel: The initial detection of a planet candidate (labeled C1) was made by Wagner and his team in 2019, using the Very Large Telescope operated by the European Southern Observatory in Chile. Right panel: In 2024, the James Webb's Space Telescope's Mid-Infrared Instrument, which uses a coronagraphic mask to block the bright glare from Alpha Centauri A, revealed a potential planet (labeled S1) on the other side of the star.

NASA, ESA, CSA, Aniket Sanghi (Caltech), Chas Beichman (NExScI, NASA/JPL-Caltech), Dimitri Mawet (Caltech), Joseph DePasquale (STScI), Wagner et al.

"We are possibly looking at a planet in the habitable zone of the closest star," he said, "and even though it's most likely a gas giant, we're still talking about a planet that could be orbited by moons in places where we could potentially envision life, existing right next door. The fact that we now have two possible detections of this planet is incredibly exciting."

Visible only from Earth's Southern hemisphere, the Alpha Centauri system is made up of the binary Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B, both sun-like stars, and the faint red dwarf star Proxima Centauri. Alpha Centauri A is the third brightest star in the night sky. While there are three confirmed planets orbiting Proxima Centauri, the presence of other worlds surrounding Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B has proved challenging to confirm.

Now, Webb's observations from its Mid-Infrared Instrument, or MIRI, are providing the strongest evidence to date of a massive planet orbiting Alpha Centauri A. The results have been accepted in a series of two papers in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

If confirmed, the planet would be the closest to Earth that orbits in the habitable zone of a sun-like star. However, because the planet candidate is a gas giant, scientists say it would not support life as we know it. Webb's observations suggest the planet is a gas giant, possibly similar to Jupiter, rather than rocky in nature.

"With this system being so close to us, any exoplanets found would offer our best opportunity to collect data on planetary systems other than our own," said Charles Beichman, NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the NASA Exoplanet Science Institute at Caltech's IPAC astronomy center, co-first author on the new papers. "Yet, these are incredibly challenging observations to make, even with the world's most powerful space telescope, because these stars are so bright, close, and move across the sky quickly."

Several rounds of meticulously planned observations by Webb, careful analysis by the research team, and extensive computer modeling, to which Wagner contributed, helped determine that the source seen in Webb's image is likely to be a planet, and not a background object (like a galaxy), foreground object (a passing asteroid), or other detector or image artifact.

In this image taken by the Hubble Space Telescope, Alpha Centauri A (left) and Alpha Centauri B shine brightly in the night sky. Located in the constellation of Centaurus (The Centaur), at a distance of 4.3 light-years, the two stars form a binary system.

ESA/Hubble

"When all you have is a dot of light next to a star, you may or may not be looking at an actual planet," Wagner explained, "but when you see a dot of the same brightness several years later on the opposite side of the star, the story becomes much more compelling."

Observations of the system in August 2024 used the coronagraphic mask aboard MIRI to block Alpha Centauri A's light. While extra brightness from the nearby companion star Alpha Centauri B complicated the analysis, the team was able to subtract out the light from both stars to reveal an object more than 10,000 times fainter than Alpha Centauri A, separated from the star by about two times the distance between the sun and Earth.

While the initial detection was exciting, the research team, which also included Jarron Leisenring, associate research professor at Steward's Imaging Technology Lab, needed more data to come to a firm conclusion. However, additional observations of the system in February 2025 and April 2025 did not reveal any objects like the one identified in August 2024. To investigate this mystery, the team used computer models to simulate millions of potential orbits, incorporating the knowledge gained during repeated observations.

Based on the brightness of the planet in the mid-infrared observations and the orbit simulations, researchers say it could be a gas giant approximately the mass of Saturn orbiting Alpha Centauri A in an elliptical path varying between one to two times the distance between sun and Earth.

The fact that the researchers were not able to spot the planet in the second and third round of observations with Webb isn't surprising, according to Wagner, as the planet was predicted be on an elliptical orbit that would have taken it too close to its star during that time.

"The observations and orbital simulations provide us with a prediction for where the planet will be in the future," Wagner said, "and the best time for us to go back and look at it will be in fall of next year. We look forward to that opportunity to confirm its identity beyond any doubt."